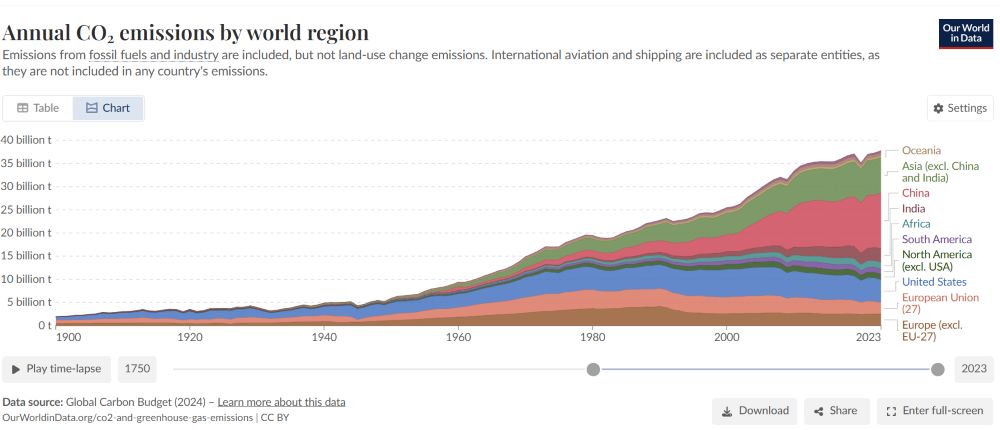

This past week, the news was carried around the globe. We humans have helped the climate break every meaningful heat record for nine months in a row. There are no medals or trophies – only fears and hopes that we can lessen greenhouse gas emissions and turn down the heat.

Last Sunday, this headline in El Pais underlined the broken records: “Six records and a 144.1ºF heat index: The beaches of Rio de Janeiro are burning: The Brazilian city recorded the highest temperature of the decade on Saturday at 9:55 a.m., fueled by humidity and geographical factors such as the nearby mountains.” The Rio Alert system noted that six temperature records were broken within a few weeks of each other.

The Guardian covered the questions that climate scientists face in “Scientists divided over whether record heat is acceleration of climate crisis.” That article explains further, “Some stress that current trends are within climate model projections of how the world will warm as a result of human burning of fossil fuels and forests. Others are perplexed and worried by the speed of change because the seas are the Earth’s great heat moderator and absorb more than 90% of anthropogenic warming.”

In either case, there is cause for concern.

Climate migrants are already on the move

One major result of the increasing heat, wildfires, flooding, and serious storm damage is an increasing dislocation of millions of people.

The Brookings Institute cautions that we need to begin preparing for climate migrants, even those who are U.S. citizens within the USA.

The Brookings think piece, “Preparing for domestic climate dislocations: What can we learn from the Great Migration?” is the first in a series. This article says, “According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, tens of millions of people will become climate migrants in the coming decades. International migration tends to get the most attention, but internal displacements will also be severe. As temperatures rise, droughts become more severe, and storms and floods become more extreme, millions of Americans will be uprooted.”

The article walks the reader through lessons about the changes in political bedfellows and economic realities resulting from this early 20th century migration of blacks to northern cities. The writer, Vanessa Williamson, concludes:

“The partisan realignment that followed the Great Migration should encourage our humility in our capacity to predict the future—a humility that can keep us from cynicism and despair.”

The worried meet in climate cafes

With all this dire climate change swirling, The New York Times reported that climate cafes are appearing to help the worried address climate anxiety. In these small gatherings, people share their worries and offer mutual support.

In a past blog post, “Confronting Climate Anxiety,” I offered some ways to address the mental health consequences of awareness that life on planet earth is at risk. Perhaps you can also create your own “climate café. “ It makes sense to accept the anxiety we may feel, but it’s best to move it toward actions you can take. We can all work together to halt the dramatic increases in greenhouse gas emissions, heat, and resulting weather disasters.

What some climate actors in government are doing

President Biden has just issued a new order on auto emissions from new cars that is certain to be challenged by the auto industry and related commercial interests. A Washington Post headline summarizes, “Biden seeks to accelerate the EV transition in biggest climate move yet: The EPA’s final rule follows a concession to labor unions worried about a rapid shift to electric vehicles, and a nod that EV sales are slowing.”

The concession backs away from a more rigorous demand, but it will still have a dramatic impact on lowering greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles. The article explains how the new order offers a workaround at a time of declining sales of electric vehicles, “…automakers could comply by boosting sales of plug-in hybrid vehicles in addition to all-electric vehicles. Plug-in hybrids have recently proved more popular with U.S. consumers, in part because of concerns about a lack of public charging infrastructure.”

States and climate superfunds

In his newsletter The Crucial Years, Bill McKibben tells of one way some states are exploring making fossil fuel companies pay climate crisis costs. In Vermont, New York, Maryland, and Massachusetts, states that don’t have major oil companies within their border, “legislators are opening up another front — ‘climate superfund’ laws.” These laws would” treat disasters like Vermont’s summer flooding as if they were a toxic dump whose cleanup can be charged to the corporation that caused them.”

McKibben says, “It’s increasingly easy to prove that absent global warming we wouldn’t have the endless downpours/droughts/fires. If a chemical company pollutes a site, the superfund law has been a way to make it pay for the remediation—so if Vermont’s flooding cost its taxpayers $2.5 billion to repair the damage caused by climate change. air, why should they be on the hook?”

Meanwhile, The Condor published “Big Oil faces a flood of climate lawsuits — and they’re moving closer to trial,” a fascinating overview of the lawsuits brought against fossil fuel companies for the damage caused by climate change. The state of California started this trend about six years ago, and there are now about 30 cases filed by cities, states, or indigenous tribes that are winding their ways through courts around the USA.